Ok, enough pretty pictures of motorbike rides through the Vietnamese countryside, it’s time for a rant about software, and systemic oppression.

First, a disclaimer: I am neither a lawyer, a doctor nor an accountant, and this should not be mistaken for legal, medical or financial advice. I am a software engineer, and you should definitely consider this advice on designing software.

My current employment status is technically “unemployed”. Ada / TSNE doesn’t have any kind of system in place for an extended leave of absence like this, so on paper I’ve quit, and they’ll hire me back in February. I worked part time through August and “worked” (spun out my vacation hours) the first half of September, so I maintained benefits through the end of the month.

Then, because my country is bass-ackwards and relies on corporations to provide what ought to be a public service, as of October 1st I lost coverage for health insurance. It’s a situation that’s given the Europeans in the hostels a lot to chuckle about.

Being a lazy git, I didn’t dive into the tangle of buying private health insurance until the last possible moment. Of course it takes time for your requests to filter through the bureaucracy, which means things had barely gotten started before I flew up Tokyo.

“That should be fine” I thought to myself. “I’ve got 60 days to get everything sorted out. Sure I’ll be doing it on mobile, but come on, it’s 2019, they must have mobile sites or at least a crummy app or something”. Little did I know.

I found a plan through Kaiser Permanente via the Washington Health Plan Finder, and got to work. My first hurdle was submitting my proof of loss of coverage, to allow me to participate in a special enrollment period. There are two ways to submit such a document: online, or by fax.

Unfortunately their website is 100% broken on mobile. The button to upload a document simply doesn’t appear. I tried a different browser, tried requesting the desktop site, all to no avail. I called their support line, but they could not help me.

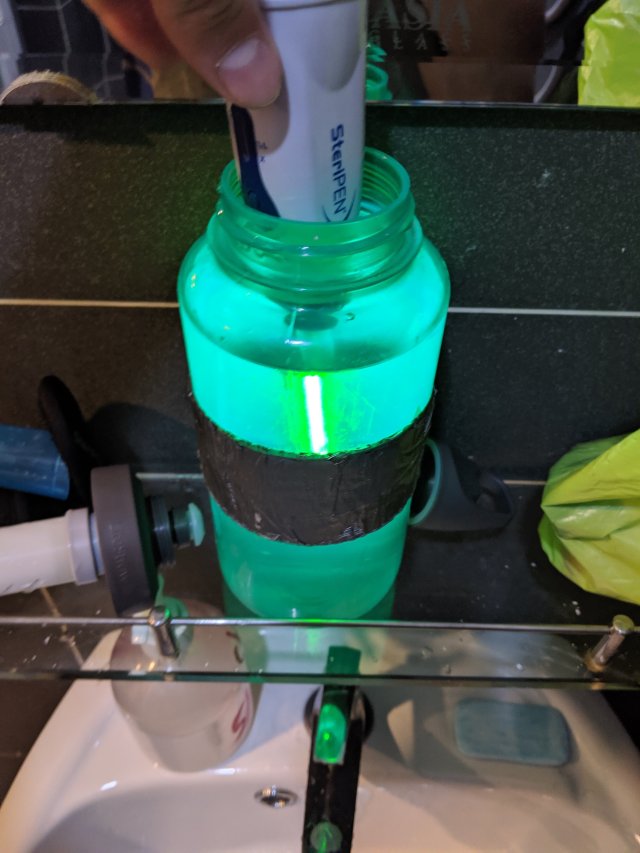

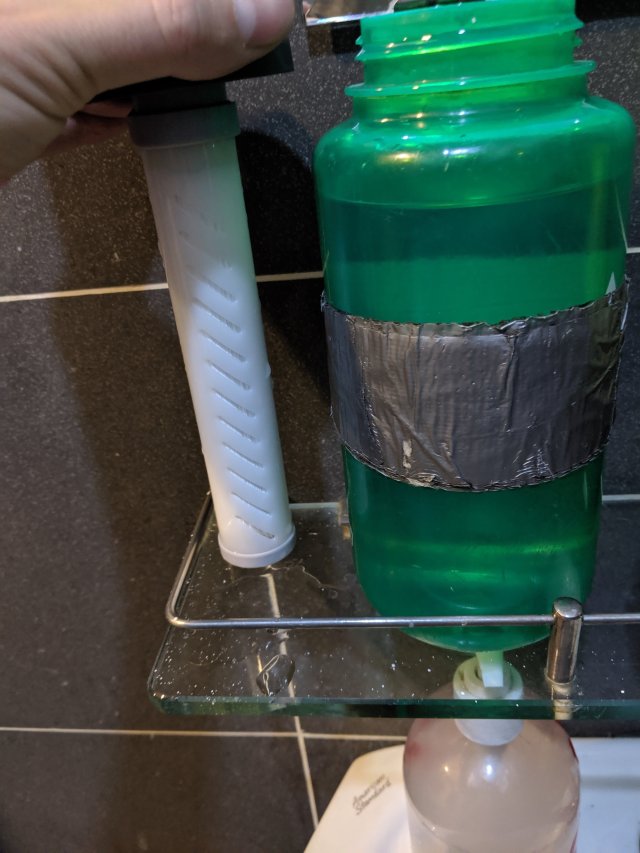

So I found a sketchy app that allowed me to send a PDF as a fax. I downloaded the file, and used another sketchy app to actually find it in Android’s filesystem so I could send it. Data probably stolen twice over, but hey at least it was free.

The next hurdle was timezones. I got no response from KP. I gave it a week, then decided to give them a call. Indochina time is 14 hours ahead of Pacific, which means 8-5 for them is 10 PM to 7 AM for me but whatever, I can stay up a little late and be the first caller.

After several hours of phone tag spread over a couple days, I finally got someone on the line who could go look in the fax basket. Oh, there’s your document! We’ll get that filled right away. Great.

A few more business days pass, and I finally get an invoice. Hooray, I can pay for something that should be included with my taxes! For two services I had to set up three different accounts, including making up at least one username (this is a pet peeve of mine – just use my email please), keeping track of passwords, etc. And oh, the horrible web design. Forms full of needless javascript that show a loading widget every time you click a checkbox. Pages that rely heavily on pop-ups and modals, and assume a desktop-sized viewport. Fields that won’t let you paste, for things like confirming your email or your bank’s routing number, or even for passwords (why would this ever be useful?).

It was, frankly, a terrible experience trying to buy insurance on mobile. I seriously considered just not doing it, going uninsured for a few months. And this is for someone who’s about as tech savvy as it gets, who understands what’s going wrong, who knows every trick in the book to convince a bad website to behave, who is well organized and uses a password manager, who is a native English speaker. I cannot imagine how bad it would be for someone who was not all those things.

The frustrating thing is, these are not hard problems to solve. Building a web form that works well on mobile has been done. There are libraries out there that will do it for free, as accessibility features like aria labels, and connect it securely to your backend, without a ton of javascript fluff. Mobile-first design is established canon. Any Ada alum could design a better website than those in a heartbeat. There is no excuse in 2019 for a bad desktop-only website.

So what? Buying insurance on mobile has got to be an extreme edge case, right? Well, not really. According to Pew Research, nearly one in five Americans is “mobile-dependent”, that is, owns a mobile device and does not own a laptop, desktop or tablet. That rate grows substantially if you look at the poor, the young, and underrepresented minorities. In other words, the people least likely to get insurance automatically through their employers. With low income people and URMs, they’re also the least likely to be tech-literate enough to cajole a crummy website into doing what they need.

Effective design takes into account the needs and capabilities of the user. If the user can’t use it easily, it’s not well designed. Often, as in the case of desktop-only websites, poor design disproportionately affects the most vulnerable among us. Often, as in the case of an insurance company’s website, this design serves as a gatekeeper to critical services and functions. When the two intersect, you get systemic oppression: a system that maintains the lines of power, that makes it easy for the rich, difficult for the poor. In other words, bad design isn’t just lazy, or ugly, or difficult to use. Bad design is racist, it’s classist, and it’s ageist.

In this case, bad design also represents a missed opportunity. How many people didn’t buy insurance from KP because they couldn’t figure out how to make the site work? How many hours of call center time were wasted?

As we design our digital world, we have a moral and financial imperative to think hard about design and usability. Can all of our potential customers use our site easily? How do you know – did you test it? Did you ask them? Where are the problems, the kinks in the pipeline, the places where those who need your service most might fall through the cracks? It is our responsibility to consider these questions, to put ourselves in the shoes of those who are different from us, to get their input and build something that works for everyone. Or if you are contacting out such a project, to find a team that will consider those questions, and give them adequate time and funding to do so. To do anything less is oppressive, wasteful, and ultimately beneath us.