Hello from Malaysian Borneo! This was a last minute addition to my trip – I had originally planned to work my way south through Thailand and peninsular Malaysia to Singapore, but I’ve met enough other travelers who were raving about Borneo that I figured I had to give it a shot. Orangutans, giant flowers that smell like corpses and one of the tallest mountains between the Himalayas and Patagonia are all right up my alley, plus part of the goal of this trip is to be spontaneous!

Well, spontaneity seems to have backfired a bit this time. Borneo is currently smack dab in the middle of its rainy season, which means I’ve traded the clear blue skies of Northern Thailand for a heavy marine layer and intermittent downpours. I did not do my research, instead assuming the whole of Southeast Asia would follow the same climate pattern. It’s a solid 2300 km between Chiang Mai and Kota Kinabalu, about the same as Seattle to Minneapolis, so clearly that assumption doesn’t make any sense. Blame it on my imperialist first world upbringing, I guess. At least it’s still warm.

Being me, I decided to face the weather head on and go climb a mountain.

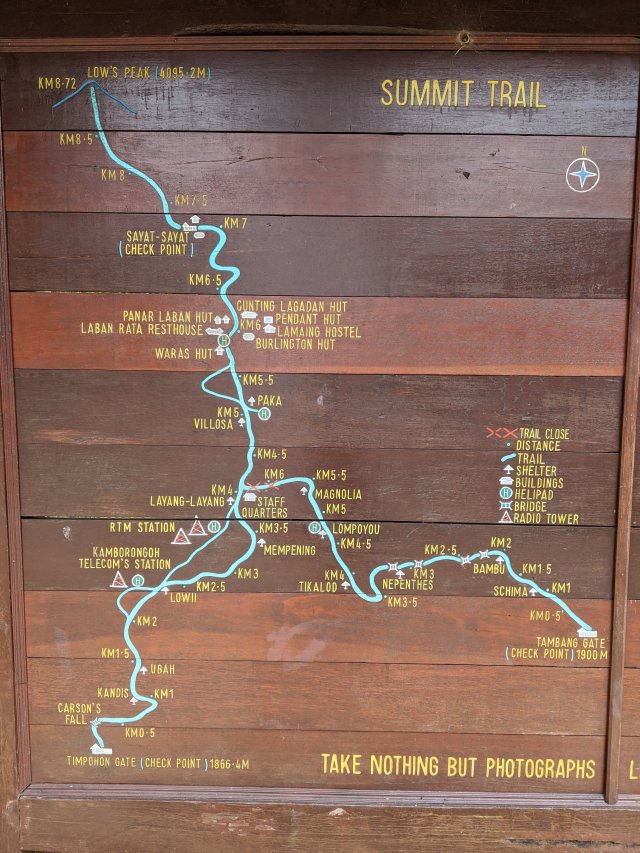

At 4095 meters (13435 ft) Mount Kinabalu is the tallest mountain in the Malay Archipelago. It’s also taller than anything in Indochina or Australia, making it the biggest peak in this part of the world. It’s just a little shorter than Rainier, but it’s tropical location means it’s snow-free year round, and the climb is not technical. The Malaysian government requires that all climbers have a permit, which in practice means climbing with a guide over two days.

In addition to our Malaysian guide, the group consisted of two Danes, a German and me. We were one of only two English-speaking groups on the mountain, out of maybe 50 or 60 climbers that day. The climbing outfit picked the four of us up from our hostels on Wednesday morning and drove us to Kinabalu Park, where the trail began at about 1800 meters elevation.

I was a little nervous as we set out. I’ve done a lot of hiking but little proper mountaineering, and it’s been difficult to keep up my regular exercise schedule while traveling. Would the team leave me in their dust? Would my asthma kick up with the elevation and prevent me from summiting? The description on the guide’s website didn’t allay my fears:

There are many who underestimate the intensity and difficulty of hiking up Mount Kinabalu. Even if one has a vast amount of experience in hiking, please note that Mount Kinabalu is going to be a different experience. It has been reported that, hiking Mount Kinabalu is equivalent to squeezing 5 days of hiking in any of the great mountain ranges into just 38 hours!

On the trail, it quickly became clear that I needn’t have worried. Though the others in the group were fit, I had far and away the most trekking experience, and after getting permission from our guide I quickly ranged ahead up the well-maintained trail. As my mother always says, when the going gets steep (and oh was this steep) everybody needs to go their own pace, anything else will make everybody miserable.

Almost as soon as we hit the trail it started to rain, and it alternated between drizzling and pouring the entire day. The trail turned to a stream, and everything not covered by my rain jacket got completely soaked. It was wet enough that I didn’t dare take my phone out of my dry bag for photos.

The first day’s trek was about 6 km, up to 3270 meters (about 10000 ft). The first 5 were fine, if quite steep. But at around the 5 km mark the trail passed 3000 meters, and I began to really feel the elevation. That last kilometer took almost an hour: take a few steps, take a few breaths, take a few more steps. Still I had made good time – when I reached the base camp just before 2:00 I was one of the first climbers to arrive; about an hour later the rest of my group came staggering in.

We ate an early dinner, then hopped into bed for a few hours sleep. At 2 AM on Thursday morning we awoke, ate again and begin our attempt on the summit for the dawn.

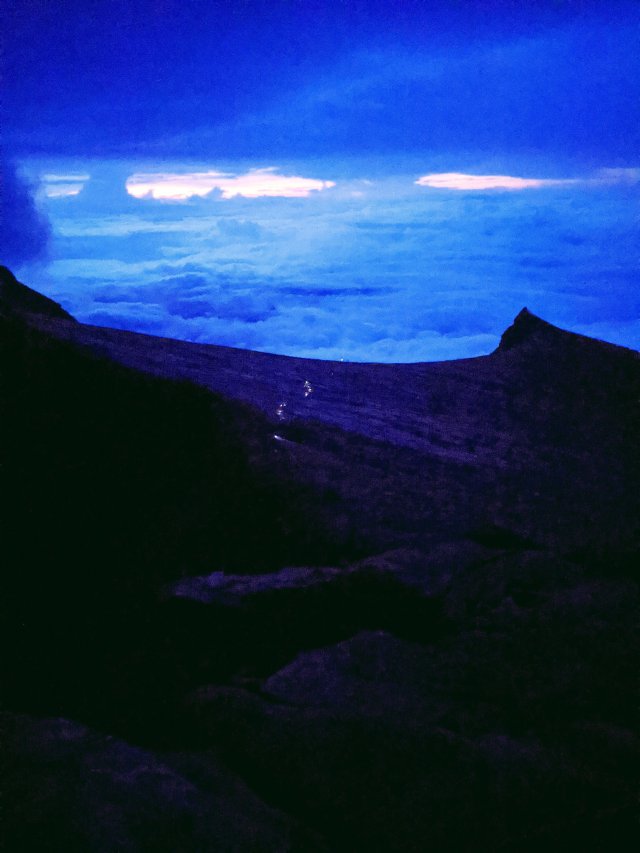

The clouds had cleared overnight, giving us a beautiful full moon to aid our headlamps, and the pre-dawn climb was quite peaceful. I had acclimated after the long rest at elevation, and though I was breathing harder than normal I wasn’t gasping. Again I sped ahead of the rest of my group, passing many Malaysians struggling up the steep route to the top. At around 5:25 I was in the first cluster of hikers to summit, half an hour before dawn. 4095 meters, just 8.5 km from the trailhead.

It was cold at the summit, just a little below freezing. Not much compared to a northern mountain to be sure, but for the second time in a week I was grateful for my warm layers. The cloud cover had returned as we climbed, and instead of warming rays the day brought only a cruel wind and bitter freezing mist. I gobbled down a snickers bar and got the heck off that ridge, snapping pictures as I went.

Breakfast back at the lodge was a welcome chance to warm up, then we repacked our bags and started the final trek back down to the road. The weather was cloudy but mostly dry, and I got a chance to photograph some what I missed on the way up.

This time I really tried to be patient and stick with the group, but with 2.5 km left to go I finally got sick of their exhausted pace and went down to wait for them at the gate. Holding myself back for safety on the steep slippery rocks that last chunk took me about 50 minutes; it was another 45 before they appeared. I will forever be grateful to Sylvester for trusting me to go do my own thing.

With a total of 17 km (10.5 miles) and 2200 meters (7200 ft) elevation gain, this was definitely the steepest hike I’ve ever done, though far from the longest. Just based on the numbers I suspect I could have done it as a long day hike, though I’m not experienced enough with altitude to be sure. Would pausing for an hour or two at lunch have been enough to acclimatize? Maybe, maybe not. Still, the overnight stay and pre-dawn ascent were a pretty cool experience, and it’s not like I’m in some kind of a rush.

Besides, I’m plenty sore even without a punishing pace.